A version of this article first appeared in the programme for the BBC Last Night of the Proms 2016.

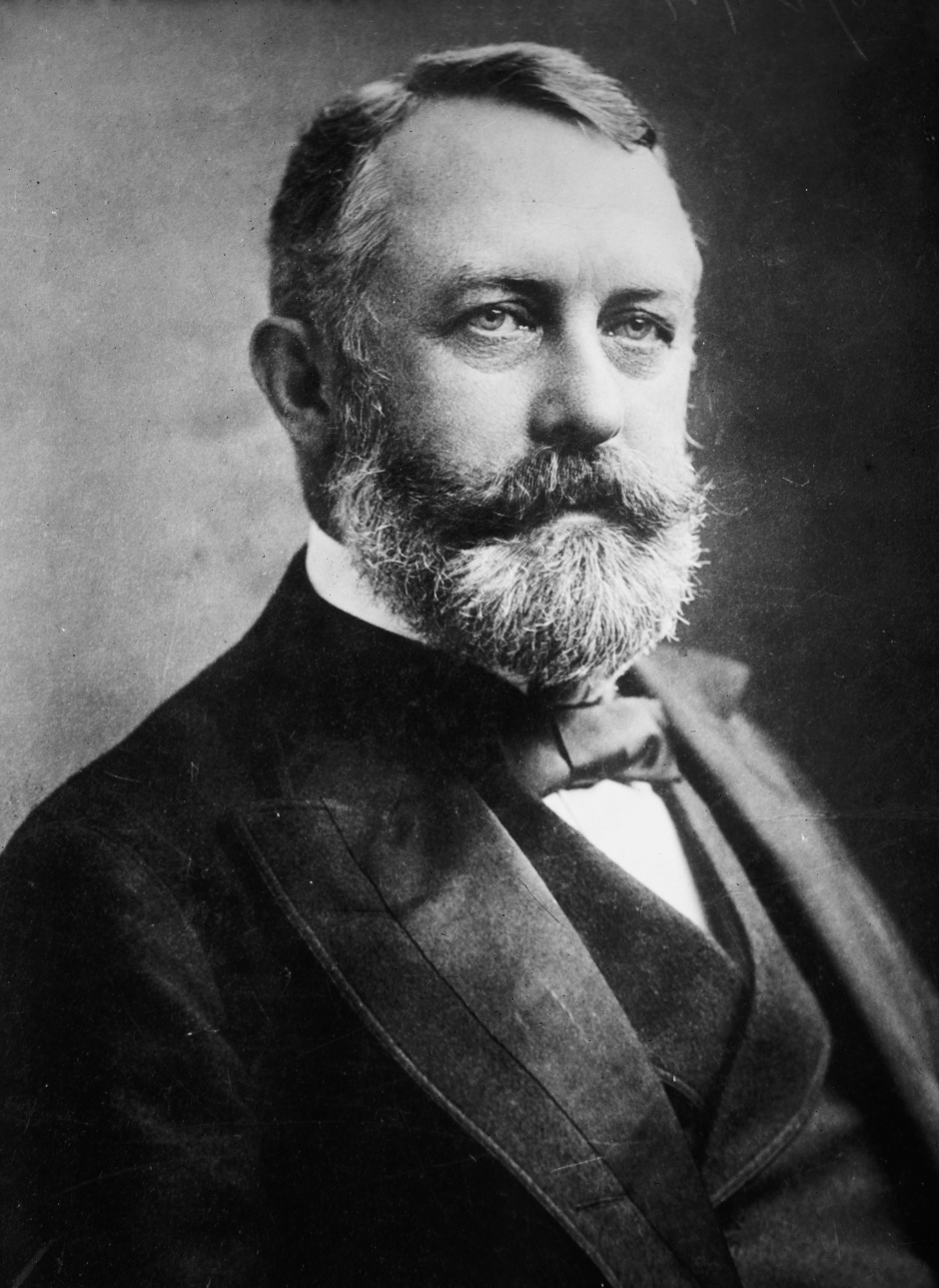

On 10 March 1916 Sir Hubert Parry completed his setting of the opening verses of William Blake’s epic poem Milton. Entitled ‘And did those feet in ancient time’, the work was commissioned by Poet Laureate Robert Bridges on behalf of General Sir Francis Younghusband’s patriotic campaigning organization: ‘Fight for Right’. Parry’s brief was to compose a unison song that an audience would feel compelled to join in and sing, and which would ultimately become an anthem to counteract First World War German propaganda and celebrate Allied victories. Premiered at a Queen’s Hall meeting of ‘Fight for Right’ on 28 March 1916 by a massed choir of 300 volunteers from London-based choral societies under Henry Walford Davis, it was an instant success. By November Parry had orchestrated the organ accompaniment and retitled the work Jerusalem for publication. However, he had always been uneasy with the strong patriotism of ‘Fight for Right’ and in 1917, after turning down further commissions from them to compose more nationalist songs, he wrote to Younghusband to withdraw his support and association with the movement. The nation had already taken to heart the stirring melody of Jerusalem, so Parry was particularly gratified when Millicent Garrett Fawcett of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies sought to perform it at a demonstration concert in the Albert Hall on 13 March 1918:

I wish indeed it might become the Women Voters’ hymn, as you suggest. People seem to enjoy singing it. And having the vote ought to diffuse a good deal of joy too. So they would combine happily.

Parry originally intended the first verse to be sung by a solo female voice so this was a happy union. He granted copyright to the Suffrage cause and its popularity increased as Jerusalem became the anthem of the Women’s Institute.

Sir Edward Elgar’s re-orchestrated and enlarged accompaniment for use at the Leeds Festival in 1922 only increased its appeal and, although Parry’s orchestration remains popular, it is Elgar’s that has become synonymous with the Last Night of the Proms. There have only been two occasions where Jerusalem has appeared earlier in the season. The first was its Prom premiere under the baton of Sir Henry Wood when it was partnered with Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens to conclude a 1942 Prom of Wood’s own arrangements of Handel and Rameau. The other was in 2009, in a performance by the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain, proving the robust nature of its identity. The arrival of Malcolm Sargent in 1947 marked a change in tone for the Last Night and its broadcast on BBC television. He oversaw the introduction of Jerusalem to the programme in 1953, symptomatic of a post-war era of increasingly rambunctious season finales. It has remained a staple of the evening and an expression of Englishness ever since, forming with Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 and Henry Wood’s Fantasia on British Sea Songs one third of the holy trinity of Last Night triumphalist music.

What Parry captured in his anthem of comfort for war-torn England was a vision of spiritual fervour. One obituary summarized Parry’s achievements, plainly evident in Jerusalem: ‘He represented in music the essential sanity of the English genius: its mixture of strength and tenderness, its breadth, its humour, its entire freedom from vacuity and affectation.’ The meaning of Blake’s text has, of course, come under regular scrutiny, some examining the apocryphal image of heaven in England, others the potential sexual or chauvinistic connotations of arrows of desire, and most forming an opinion on the identity of the dark satanic mills; but the musical setting has rarely been criticised. While the words are open to interpretation, Parry’s music has clearly rendered the sentiments decent, God-fearing, and magnificent. When introducing Jerusalem to Walford Davies in 1916 Parry himself pointed to one of the highlights: ‘he put his finger on the note D in the second stanza where the words ‘O clouds unfold’ break his rhythm. I do not think any word passed about it, yet he made it perfectly clear that this was the one note and one moment of the song which he treasured.’ The collective emotion that sweeps through the raised unison voices of a full hall is an honest elevation of collective hope. Little surprise then that it was the only one of the Last Night trio performed immediately after the tragic events of September 11, 2001, and fitting that in its centenary year it has been posited as the national anthem of England. Ultimately Jerusalem is the melody that re-echoes at the end of the Last Night; a sentiment foreseen by Sir Henry:

And as each Last Night of the Season has come round and I have been almost mobbed and my car pushed out into Langham Place by a crowd of jolly young men and girls, I have realised increasingly with the years that music is a great power in England: that there are hundreds of young people who have discovered what their fathers discovered – that the best melodies are in the best music.

Henry J. Wood, My Life of Music (London: Gollancz, 1938), p.193

Photo credit: Alwyn Ladell http://bit.ly/2clZjvY

=